Project 1: Sociology Inter-textbook/Create-Your-Own-Textbook

Intro: In an effort to diminish the power of heavy, pricy, and boring textbooks in an intro class, I propose an online ‘inter-textbook’. Students will use the Internet’s many ‘texts’ (written, pictures, videos, audio, games) to create their own chapters on a very large online cork board-type space (similar to padlet.com). As the professor, I would provide lots of structure, like taking the main concepts found in one textbook chapter and setting them up on the board in a logical manner, and guiding the students to figure out what is a good source and what is an unreliable source of information. The students will then post (under their assigned concept) any relevant texts (online articles, blogs, videos, pictures) that provide the definition of the concept, examples of the concept, people associated with the concept, etc. Students will also be required to comment upon and question the postings of other students and thereby engage in a dialogue about their interpretation of the concepts. To make this as close to a traditional textbook as possible, the questions on any quizzes or tests will relate directly back to the boards they create. In short, I envision this as a space for students to create their own chapters, still working with the concepts that any traditional textbook would contain, but making it their own by posting texts that make sense of the ideas to them and engaging with other students about the validity of their sources and the level of understanding they have about the concepts. Class time would be used to go over the board the students have created during the week and fill in any gaps or correct any inaccurate information.

Personas:

The Always-Onliner: This person is always online, using his/her cell-phone in class to either check Facebook or fact-check things said in class.

The Never-Onliner: This person is only online if required to be for either work or school.

The Google-master: This person will google anything and everything, and is very adept at searching online to verify an opinion or a fact.

The Left-field thrower: This person talks about things that are usually irrelevant to the ongoing discussion, with lots of colorful personal anecdotes.

The Minimalist: This person always questions the purpose of any school-work, only does what is required and does not care about the learning process.

Use case scenario: The ‘inter-textbook’ would be found by entering a link on a web-browser. Ideally, log-in will not be necessary. If a log-in is necessary, that information will be provided to the students along with the link.

The Always-Onliner: This person would easily find the site, perhaps by clicking on a link provided by the instructor in an email. S/he would not have any difficulty logging in, if needed. S/he would have a short learning curve, mostly involving getting used to the controls on the site. S/he would most likely be a prolific linker – comfortable with linking to many types of online media.

The Never-Onliner: This person may have some difficulty understanding the mechanics of the project. S/he may be able to easily find the website by copying and pasting the link provided by the instructor in an email. S/he may have a long learning curve when trying to get used to the controls on the site, and s/he may not be very comfortable posting things like videos and pictures. S/he may also not be (at first) comfortable clicking through links provided by other students.

The Google-master: This person would be able to find the site easily by clicking through the link provided in an email by the instructor. S/he may have a somewhat longer learning curve (but not as long as the Never-Onliner) when trying to use the controls on the website. S/he would most likely be a prolific linker – comfortable with linking to many types of online media.

The Minimalist: This person would be one of the last students to open-up the link or log onto the website (if that is the case). S/he would most likely lose their log-in information or the web-address multiple times – sometimes using this as an excuse to not do work. S/he would have a long learning curve when using the controls on the site, and when trying to find and post relevant links on the site. Unless given a high incentive to, this person would most likely never click through links provided by other students.

The Left-field thrower: This person may be able to access the website without any problems. S/he may have a somewhat longer learning curve, but mostly due to not following instructions well. When engaged in doing work on the site, this person will most likely post links, videos or pictures that are only tangentially relevant to the concepts. The links this person posts may confuse other students trying to get a good grasp on the concepts.

Full-Fledged version: For a full-fledged version of this website, I will want to create a web-application using a development framework like Ruby on Rails. Since Rails is an open-source framework, I would simply download it for free. Creating something from scratch would give me a lot of control to build a user-interface that would balance intuitive use with the major requirements for the project (posting, sourcing, linking, commenting, editing). There would be a log-in process, with just one username and password for the entire class. Creating and managing multiple ‘boards’ or ‘walls’ for all the chapters would be easier, and I could set up an intuitive linking system across chapters, with a table of contents. Having control over the back-end of the site would also make it possible for me to tweak it further as the project rolls out over the semester.

Time assessment (full version): Implementing the full-fledged version will most likely take 6 months. This will involve learning Ruby on Rails, experimenting with simple designs on Rails, building a prototype of the inter-textbook (one chapter), implementing the prototype (as a class assignment with a current class), working out any problems that would arise, and completing the final version (with all chapters).

Stripped-down version: For a stripped-down version, I would use web applications that are already out there, for example, Padlet. Padlet is free to use, and it automatically gives the user a unique wall-space that can be shared with any number of collaborators. The user-interface is easy and intuitive, and walls can be made ‘private’ for use by a specific class. Since this web application is modeled as a ‘one wall/one project’ system, it may be difficult to create and manage separate walls for each chapter of the textbook, as each chapter may require a separate wall and therefore a different web-address.

Time assessment (stripped version): Implementing the stripped-down version will most likely take 3 months. This will involve learning and experimenting on Padlet, building a prototype wall (one chapter), implementing the prototype (as a class assignment with a current class), working out any problems that would arise and completing the final version (with all chapters).

Project 2: Culture-Jamming/Meme-Building

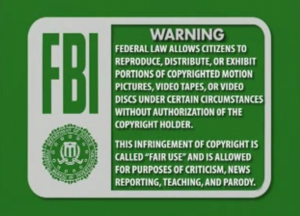

Intro: Applying sociological concepts to everyday activities and messages is one of the hardest skills to instill in intro level students. I’ve been thinking about how students can use the everyday material that is presented to them online and remix it to create sociologically relevant messages. ‘Culture-jamming’ is a technique used by activists who engage with mainstream messages (especially advertisements), point out the fallacies inherent in those messages, and sometimes change the script of those messages to relay the truth about a specific product or service. ‘Memes’ are continuously reproduced cultural messages, usually visual in nature with some changeable text, that are often found on social media sites. Memes are also a highly effective way of learning and reproducing the transient cultural norms of the time. Students in an intro level sociology class will learn how to build memes, and produce sociologically relevant memes to spread on social media sites. Each week, students (working in teams) will look for memes relevant to the topic of the week and culture-jam it to convey a sociological message instead.

Personas:

The Reddit-Obsessed: This person is obsessed with both looking at and perhaps even tweaking memes. They get all of their entertainment, socialization and even news from Reddit or Tumblr, sometimes even forgetting to eat because of an online flame-war.

The IRL-Centric: This person is only online if required to be for either work or school. S/he makes it a point to not create any online social-media accounts for fear of privacy violations, becoming addicted to social-media or discomfort with online technology in general.

The Activist: This person is always highlighting and critiquing the social-economic-corporate conspiracies in society. S/he is frustrated by the social construction of race, gender, class, social institutions and society in general.

The Culture-is-Natural-ist: This person thinks that the cultural norms prevalent in society today are just the way things have always been, and a reflection of natural laws. S/he is unable to see the social script at work when they come across cultural memes.

The Minimalist: This person only does what is minimally required, his/her only goal is to pass the class, and s/he does not care about the learning process.

Use case scenario:

The Reddit-Obsessed: This person will be the most prolific meme-maker, or at least understand the concept and the mechanics behind meme-building more easily than the rest. S/he will have the shortest learning curve, but may still struggle with making the memes sociologically relevant.

The IRL-Centric: This person will most likely be the most hesitant to participate in the project. It will require a lot of hand-holding to get this person on board to at least look for and put forth ideas for tweaking memes. Even so, s/he may be very uncomfortable promoting the meme that his/her team creates on social media.

The Activist: This person will be readily convinced to culture-jam popular memes, and may even suggest ideas about how to change the messages of the memes to reflect sociological perspectives.

The Culture-is-Natural-ist: This person may be the most hesitant to critique or think about changing the messages that are conveyed in popular memes. S/he may even buy into the cultural script the meme promotes, and if s/he tweaks any memes, s/he will tweak to reflect the same cultural script as the original meme.

The Minimalist: This person would never look for current memes, initiate any ideas about changing memes, or try to do any technical work in tweaking the memes. S/he will depend on the work of more engaged students.

Full-Fledged version: For a full-fledged version of this project, I will want to provide the students with a few workshops on using advanced meme-building tools like Photoshop (proprietary software) or Editor by pixlr.com (free web application). To ensure that students are ready to engage in meme-building I would also set aside some time for them to practice in class (in a computer lab) and assess their final products for a grade. Although Photoshop and Editor can be used to tweak existing memes, they are more geared toward building memes from scratch.

Time assessment (full version): Implementing the full-fledged version will most likely take 3 months. This will involve learning Photoshop or Editor, experimenting with simple designs on either application, building a prototype assignment as a team-project, implementing the prototype (as a class assignment with a current class), working out any problems that would arise, and completing the final project design.

Stripped-down version: For a stripped-down version, I would use simpler meme-building web applications, like, the Imgur meme-generator. Imgur is free to use, where a user is able to either borrow background images from current popular memes, or upload their own images. The user-interface is easy and intuitive. Although Imgur can be used to build new memes, it is more geared toward tweaking existing memes.

Time assessment (stripped version): Implementing the stripped-down version will most likely take 2 months. This will involve learning and experimenting on Imgur, building a prototype assignment as a team-project, implementing the prototype (as a class assignment with a current class), working out any problems that would arise, and completing the final project design.